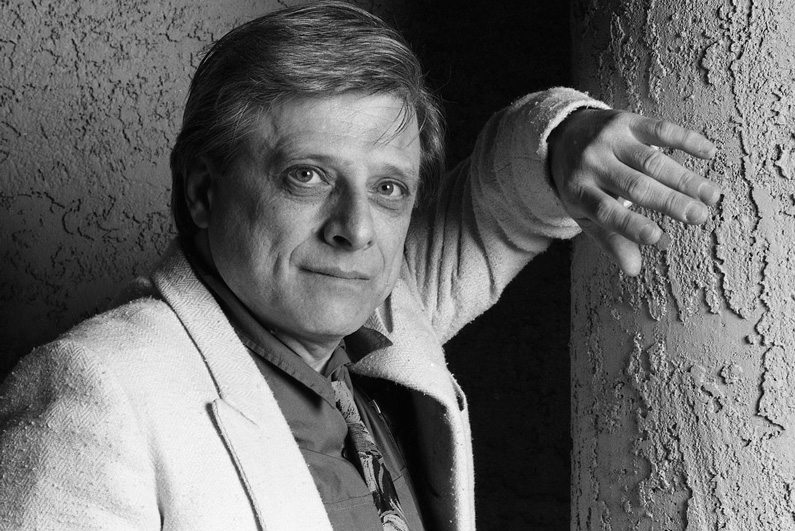

The singular quality of Harlan Ellison's writing—articulated with affection and precision in this lovely piece by Carol Cooper in The Village Voice, posted shortly after he passed away on June 28, 2018—was in prose that sings with eloquence and wit and burns with edge and passion; a passion for what is right and good; for the strength and necessity of kindness and intellect and reason; for the continual unwillingness to be meek in the face of injustice everywhere, big and small, personal and political.1

Embed from Getty Images

But beyond that was something more. The personality. The performance. The charisma. The honesty. The raw emotion. The righteous anger. And the range: Harlan combined vulgarity with subtle intellectual engagement in the same sentences, about the same things, recognizing the truth of those opposites in each of us and expressing them fearlessly. He was unafraid of fullness and difference. His work crossed boundaries and categories and genres.

Harlan spoke of writing as a job like any other job, to be done with regularity and commitment, but it was also a fire that burned hot and bright for him; a wound bleeding; a sword ready to strike. His work was alive and explosive, smart and cool, dangerous and provocative, literary and hip. The fire of its sentences burned in your blood and its sheer life—its sense of danger and passion, its entertaining vigour, its commitment to artistic and moral truth—left an impression like nothing else.

I remember in high school we were given the assignment to read Thomas Hardy’s Mayor of Casterbridge and the teacher who assigned it said—in a moment of Ellisonian honesty—that it was a particularly dull book, and yet we were forced to read it, to consider its quality, to take it seriously as something from the canon of great works. At the same time, I was discovering my own forms of fiction and art entirely separate from anything “canon”—comics and fantasy and science fiction and film, along with the firebrand intensity and uncategorizable greatness of Harlan Ellison.2

The school curriculum became the rule-bound, the circumscribed and dull and necessary, set off against the unbridled and the imaginative. It was the latter that had lasting effect, and a potentially transformative potential. And it was as if Harlan, in all his indestructible rebelliousness, represented the endlessly entertaining face and voice of that undiscovered territory, while also recognizing the best of everything that had come before.

It is in this breaking of barriers—in this traversing of the old and the new, of the high and the (supposedly) low—that I find Harlan's inimitable voice ringing continually and joyously in the background of my mind; a voice calling out ceaselessly for the value of art, for its ability to be passionate and smart and entertaining, for it to be fearlessly angry and emotionally raw, for it to be ceaselessly engaged with the world rather than detached from it. Never dull. Never tired. Always present. Always fighting. Forever and always alive.

1. These comments leave out any of the negatives that are associated with Harlan's volatile personality, and the degree to which the passion and edge in his work created a (necessary?) dark side in his life. That topic is handled in an articulate and honest way in the 2008 documentary Dreams with Sharp Teeth. I can hardly improve upon the comments made in that film, by Harlan and others, or in these words once spoken by Claire Lispector: “Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” ↩

2. I met Harlan briefly in 1989 at a convention in Toronto (that also featured Will Eisner and Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez) and was able to tell him how much I appreciated the power of his work, while also seeing him deliver a lecture, his voice at times on the edge of tears, based on his essay Everything I Know About My Father (the print version of which is in The Harlan Ellison Hornbook.) ↩